Photographing The International Space Station

One of my many interests that I had as a kid was the stars. I remember going on late night hikes as a scout and watching them migrate across the sky. On one occasion we did a dusk to dawn night hike during the Perseids, which has just happened for this year, and seeing dozens of meteors leaving trails across the sky. As with most child interests other things soon come along and my interest in the sciences was stolen away in the 90s when computers began to really take over the world, but it never truly went away.

Recently, through my interest in photography, I began to be drawn back to the stars thanks to some of the amazing astrophotography being done over the last couple of years. The Astrophotographer of the Year run by the Royal Observatory at Greenwich has had some great images and the book is worth a look.

Due to light pollution where I live what I can photograph without some specialist kit is limited, they need to be comparatively bright. 2 such objects are the moon and the International Space Station, or ISS.

First some details. The ISS is a 73 x 109m tin can, 413-418km up and is travelling at around 7.66km a second (faster than any bullet by a significant margin). An average pass is over in between 3 and 5 minutes depending on the angles involved and where the sun is.

My initial experiments with photographing the ISS where simple long exposure shots to track the ISS as it’s crossed the sky. With a bit of planning using some online tools you can be set up before it even crosses the horizon. Then it’s just a simple case of locking the shutter on continuous and then stacking the images using the lighten blending mode in GIMP or Photoshop.

Early evening passes show little in the way of stars and the ISS can be quite faint, but later the ISS become really quite bright. When shooting later you also get star trails as the ISS will take around 2 minutes to cross the frame.

I quickly realised that while the long exposure images where fun to do, I really needed a better foreground interest then I could get from my front door. After seeing a few images on talkphotography.co.uk I decided to attempt a closer image.

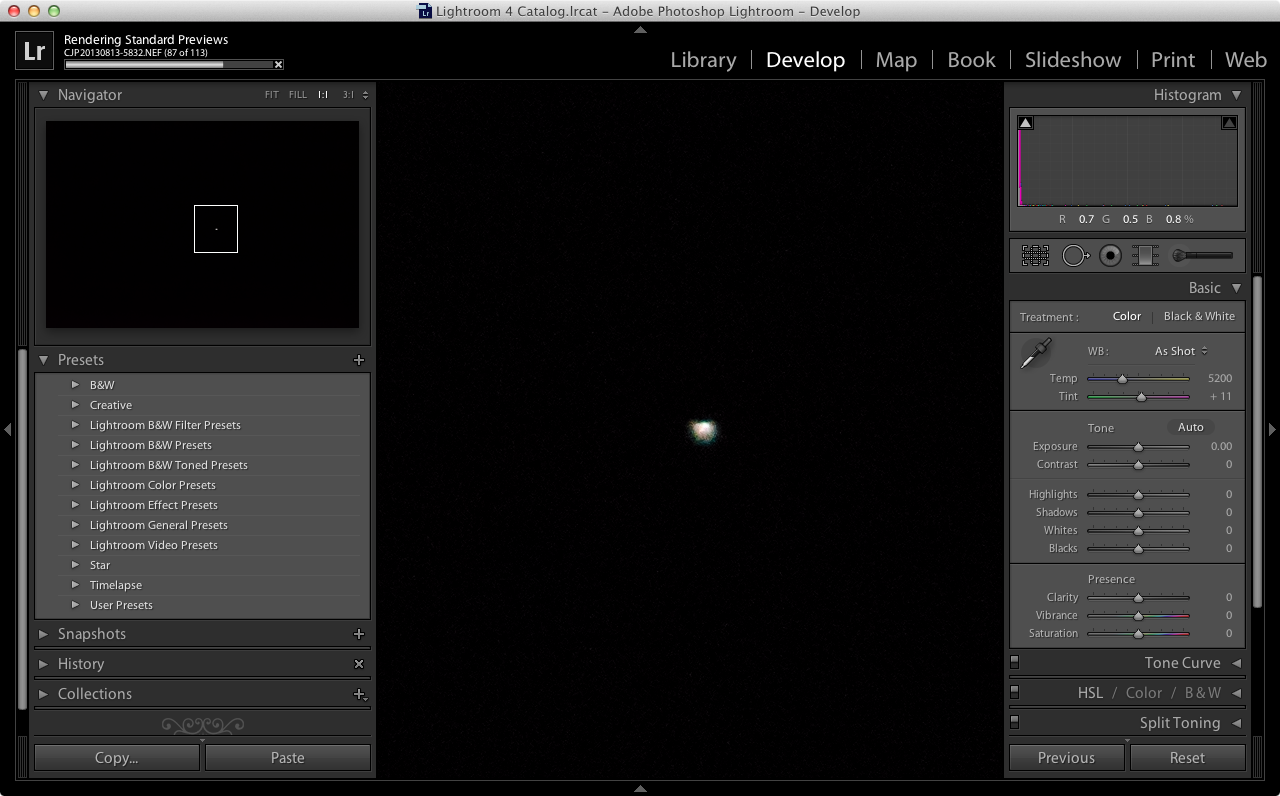

Equipment wise I used a Nikon 300mm 2.8 VR II with a TC-20EIII teleconverter on a D7000, this is all mounted on a Wimberly head on a Gitzo 3 series tripod. The technique I used is to remove most the slack in the head by tightening the knobs to help smooth the tracking then fire of burst at full frames per second when I was tracking well. The idea here was to take lots of frames and hope that a few would work out. Focusing was a touch tricky initially but once the moon came out it became easy, focus on the moon the swap to manual to lock it in.

As the ISS is lit by the sun it’s actually quite bright, sunny 16 rule bright in fact. Though as I already mentioned, it’s moving fast so you need a high shutter. Early experiments led me away from the sunny 16 area and all I was getting was bright blobs with lots of what looked like flare. I couldn’t work out what I was doing wrong!

After a few nights I realised it WAS flare, the ISS was so bright I need to tame down my settings. In the end I came to 1/4000 (did I say it was fast?) f8 ISO 800. This was enough to expose the ISS with out it becoming a big blob but also fast enough to freeze that amazing speed! What also turned out to be essential was to wait for the ISS to be over head. Closer to the horizon not only was it dimmer but it seemed more prone to being a blob, I would assume due to atmospheric interference.

dk

Am I happy with the image? I’m ecstatic, but I know where I can do more. First 600mm isn’t enough, I need 1000mm (500mm and the 2x) or ideally 1200mm (600mm & 2x). This would make the ISS bigger on the sensor but the down side is it would be up to 2x harder to frame the space station and then track it. A full frame camera won’t help here as ISO just isn’t an issue! In fact it would hurt you do to the massive crops involved and the lower pixel densities on most FX cameras.

I hope I never grow tired of this floating tin can, and I look forward to trying to improve on my image.